How Great Female Math Teaching Creates a More Just Society

- Educating Gender

- Nov 11, 2019

- 6 min read

**By Bill Davidson Guest Blogger

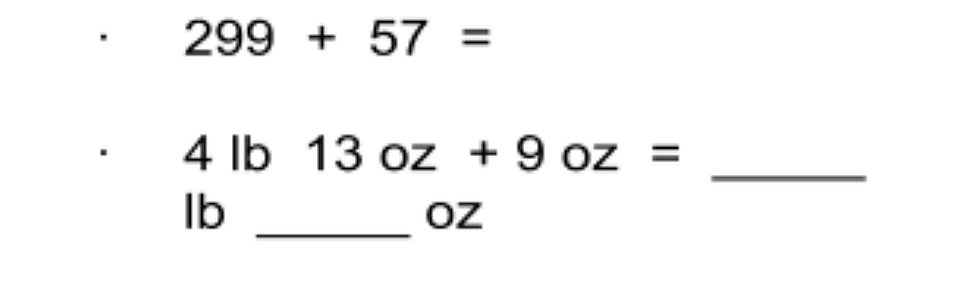

“I’m going to project two problems that I’d like you to solve on a piece of scrap paper,” I said, standing in front of a blank white board.

I was beginning a two-hour professional development session with an elite private school. Their principal had hired me to spend the school year training the K-5 teachers in elementary math teaching methods, and this was our initial meeting.

The two problems on the right would be a catalyst to understand the importance of instructional shifts, leading to flexible thinking.

Before I could begin writing any of the problems, I was interrupted.

“Ohhhhh,” said a veteran kindergarten teacher sitting in the back corner of the room. Her voice was shaking, her hands trembling. “Not math! Please…no math!”

I was less than five seconds into my presentation, hadn’t yet written a problem, and had already lost one of my participants – a teacher who knew that she was attending a math training.

***

I love my job, but it shouldn’t exist. As a math teacher trainer, I am tasked with helping educators improve their instructional delivery, but also deepening their understanding of elementary mathematics. Both are glossed over in teacher education programs and this reality has a residual effect on students - especially girls. This is because a third, seldom-mentioned part of my job is to develop teachers’ mathematical confidence, which – in a woman-dominated profession – is staggeringly low. Too many young girls don’t have female math role models, and this perpetuates the Math is for Boys stereotype.

I benefited from these social [gender} constructs both as an elementary school student and teacher.

Most educators who love mathematics and want to teach gravitate towards middle or high school rather than primary instruction. This leaves elementary schools with a literacy-centric teacher population, many of whom got into the profession because they want to offer their students a different educational experience than they received. By deemphasizing math, teacher education programs send a clear message to their aspiring educators: he subject isn’t that important. As a result, many program graduates enter their careers without a clear understanding of the math content they’re teaching or how to deliver it. This leaves them to develop their practice by sorting out memories of their schooling and/or educational literature, which is heavy on theory but light on application.

The majority of primary school teachers received traditional math instruction when they were elementary school students. The subject was taught through mnemonics and procedures; speed and memorization were celebrated and the most confident, assertive students thrived. The environment drastically favored boys, who were groomed for this type of instruction, both inside and outside the home. Today, more and more parents raise their daughters to be heard, not just seen, and gender equity has extended to arenas such as youth sports, where – from a young age - children are taught to be competitive and confident. Both of these factors would help some girls thrive in traditional math classrooms, but this type of instruction is no longer valued.

Math as memorization now yields to higher order thinking and conceptualization. These new demands require educators to embrace an academic study of the subject and willingness to undergo pedagogical shifts. During my 12 years of math consulting, I’ve found that men – at least extrinsically – demonstrate far more confidence in doing both. That’s not to exalt male teacher character while denigrating females. It simply speaks to the underpinnings of societal and educational traditions, i.e. men tend to feel empowered in a female-dominated workplace.

I benefited from these social constructs both as an elementary school student and teacher.

They [male teachers] are unicorns in elementary schools and thus garner more student, and sometimes administrative, attention than their female colleagues.

In primary school, I loved math races such as Around the World and massed practice worksheets that earned me hard candy when I completed 100 problems correctly in a minute. As the lone male teacher of a charter school math department, I was quick to speak up at staff meetings and felt like I was endowed success in whatever school endeavors I tried, a common reaction of white males working among predominantly non-white females. Therefore, when our team was trained in Singapore Math (long before it became trendy in the U.S.), I had little doubt that I could master something that initially seemed confusing to me.

My trainer, Dr. Yoram Sagher, took note of my fervor and – two years later – asked me to work as his assistant on a pilot program. At the time, I felt that I was deserving of such an honor, but I later learned that this was much more representative of my privilege than it was talent. Dr. Sagher and I both failed to recognize a female colleague who had a higher aptitude for the subject and received far better student results than me. Consciously or subconsciously, the assertive male (me) was provided an opportunity in favor of a more deserving female colleague. Together, Dr. Sagher and I perpetuated misogynistic math.

Most male teachers that I’ve trained carry themselves with a similar self-assuredness. They are unicorns in elementary schools and thus garner more student, and sometimes administrative, attention than their female colleagues. Consumed with confidence, they carry few doubts of their ability to take on the subject’s demands just as they did during elementary math classes. Possessing less mathematical confidence, many women default to their pedagogical comfort zone, delivering math instruction the same way they teach Language Arts. This becomes problematic for student learning.

The cumulative nature of math makes it different than other school subjects. Depending on the topic she is learning, a strong student can quickly become a weak student if they lack certain foundational understandings. Consistent informal assessments are therefore necessary, and this dictates the mode of quality mathematical instruction. To routinely gauge student comprehension, teachers need to sustain a demanding presence for long periods of time. This is challenging if they aren’t comfortable with the content they’re teaching. Frequently showing off understanding requires students to be independent, confident, and assertive. Boys are consistently expected to be all three. Girls are often discouraged from developing these traits. Societal norms are changing, but subconscious traditional gender role reinforcement remains in many schools.

Although they might not be able to articulate their observations, students sense when their teachers feel uneasy delivering lessons. It’s demonstrated by canceling math class on days with abbreviated schedules, overusing counting songs, fraction field trips to pizzerias, and creating projects that are only tangentially related to the subject. Although grossly unfair, when female teachers do the aforementioned, the Math is for Boys stereotype grows.

Students start blending their teacher’s discomfort with mothers who defer math homework help to fathers. They have heard the phrase I’m not a Math person uttered dozens of times, but never once by a man. In time, they come to realize that they rarely – if ever - see women as math role models.

If 30 years from now gender stereotypes are rarely coupled with mathematics, then Madge Goldman and Robin Ramos may be two of the biggest reasons why.

I likely would have fallen into many of the same trappings were it not for a few chance encounters. Madge Goldman, the president of the Gabriella and Paul Rosenbaum Foundation and one of the first women admitted to MIT, sponsored Dr. Sagher’s training, which led me to become a self-employed math consultant. Ms. Goldman, a brilliant woman and generous benefactor of our charter school, made me abundantly aware of the privileges I enjoyed, humbling me in the process. She introduced me to Robin Ramos who, along with a cadre of amazing teachers – most of whom are female – created the first Common Core-aligned mathematics curriculum - Eureka Math. Robin’s curricular writing and training has inspired tens of thousands of female educators, who are ushering in a generation of superior math students – both male and female. If 30 years from now gender stereotypes are rarely coupled with mathematics, then Madge Goldman and Robin Ramos may be two of the biggest reasons why.

In this ideal future, my work would likely not exist, or at the very least look drastically different. Every summer, I run a week-long teacher grade level workshop series, with one evening being reserved for math coaches. The former is flooded with female participants, while the latter is disproportionately weighted with men. This year, I’m working with a school, whose principal has me coaching five female teachers but none of the males. Confidence aside, I see little difference in the delivery or student results between the men and their female colleagues.

The Math is for Boys stereotype continues.

Few teachers are as candid about their mathematical insecurities as that private school kindergarten instructor, but her reaction is representative of many elementary educators’ feelings towards the subject. When I visited her classroom a month later, she proved to be an incredibly capable educator when provided some simple guidance and reassurance. I was left to wonder how great she might’ve been had she not developed math-phobia early in life and carried it with her throughout a 25-year teaching career.

For now, we are left with a sad reality. Mathematical content experts are outliers in elementary schools, and this disproportionately damages girls’ learning. Children who are taught by women that embrace the subject with skill, passion, and urgency are rare and lucky. They not only become better mathematicians, but also citizens. Seeing their teacher as confident, clever, and challenging, they learn to regard the gender equally and become stewards of a more just society.

**Bill Davidson recently began his 19th year in education - ten as a classroom teacher, nine as a math teacher trainer. After teaching in Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Southern Sudan, he has led professional development in 19 different states, Canada, and Malaysia. He has also published 39 curricular books. For more information about Bill Davidson's work, see: www.teacherbilldavidson.com

Comments